In the old days, cabinetry was actually called ‘joinery,’

because at it’s heart, that’s what it is – putting pieces of wood together in

as permanent a way as possible.

And so we have been learning the fundamentals of that

process, beginning with mortise and tenons (through-mortise, haunch-mortise and

stop-mortise) – a basic, fundamental joint that looks like this:

A day after that, we had our first lesson on dovetails. And many

of us, including myself, slept restlessly the night before. It’s intimidating.

Dovetails are simple, yet complicated, fragile, yet incredibly strong when

mated, and though many amateur woodworkers claim to be able to make them, few

have mastered the skill.

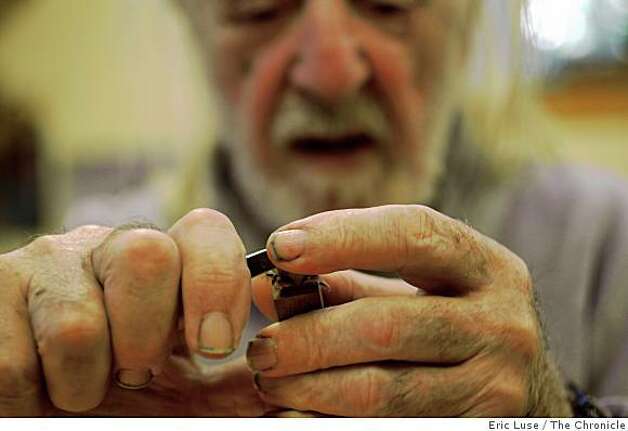

Of course, our instructor Jim Budlong made it look easy,

marking out, sawing, then chiseling a set of near perfect dovetails in front of

the entire class, in about 20 minutes.

|

| Instructor Jim Budlong demonstrates proper dovetail-technique. True story: He once tried to mess up his dovetails in order to show the class how to fix them -- but accidentally made perfect ones. Amazing. |

It took the rest of us, and myself, much longer to get

anywhere near acceptable, let alone perfect.

A dovetail joint is considered a ‘mechanical joint.’ It’s

called that because two pieces of wood are held together not simply by glue or

dowels, but by a series of pins and tails that lock together in such a way that

the pressure exerted on them, say in a dresser drawer, actually serves to make

the joint tighter over the years, not looser.

But because of that, they are difficult to make, with

complicated angles and often dozens of surfaces required to meet perfectly in

order for the join to look good.

There’s a reason perfect dovetails are seen as a mark of

true craftsmanship, even though they are usually hidden away in the back of a

drawer in a cabinet or dresser. When done well, they are sophisticated, beautiful, and add

strength and durability to a piece of furniture for decades, even centuries to

come.

Done poorly, they can cause fractures or cracks as the two

pieces of ill-fitting wood are forced together. If the dovetails themselves are

too small, too thin, their strength gives way to fragility. If the dovetails

are too large, too evenly spaced, or poorly laid-out, they become clunky and

awkward to the eye regardless of how perfectly they were cut.

In the examples we were shown from past years’ students,

there is one that was particularly disheartening. A set of dovetails, perfectly

cut, fitting together like a glove, were labelled by some heartless instructor

as being “too perfect, looks machined.” Unbelievable!

A dovetail, at its best, is not cut on a router jig or by a

giant machine in a factory somewhere. Rather, it’s the work of a careful

craftsman who cares about little details, such as the size of the pins and the

fact the pins on the outside of the joint should be closer together than those

on the inside, because there is greater stress.

A craftsman knows these things and takes them into account,

and the final product reveals that. A drawer cut by a machine simply doesn’t

have the same effect. Or at least that’s what we’re being taught, brainwashed

really, as our instructor joked recently.

I’ll take it. The challenge is fun, despite the frustration,

and getting it right in the end is so worth the effort.

And the hope is that all these various components of our

woodworking education, from sharpening to tool-making, planing and joinery,

will all add up and eventually come together, like the two sides of a dovetail

joint, and create a firm, long-lasting bond that will only get stronger in the

years to come.

|

| Some of my many dovetail attempts! |