I heard it said last night that in woodworking, when you

think you’re 90 per cent done, you have 90 per cent of the work still left to

do. That proved to be true the

past couple of weeks.

Myself and other students have been putting in crazy hours

to try and finish up all the details by the holidays (which started yesterday).

I knew I had a lot of work to do, so I decided my goal was

to have the doors hung on my cabinet, the back panel glued in, the drawers fit

and all the necessary repairs and clean up completed to the outside.

That would leave just door handles and drawer pulls, and

making racks to hold the pipes, which will be on display in the cabinet. But I

was okay with leaving those tasks until after the holidays. The real deadline

is Feb 1, when our pieces will be on display in the mid-winter exhibition, so

there will be some time to finish up in January.

Fitting a couple of drawers so they open smoothly and stop

where they’re supposed to, hanging doors so they swing open evenly and close

with a gentle click – these are things that sound simple. But they aren’t, of

course.

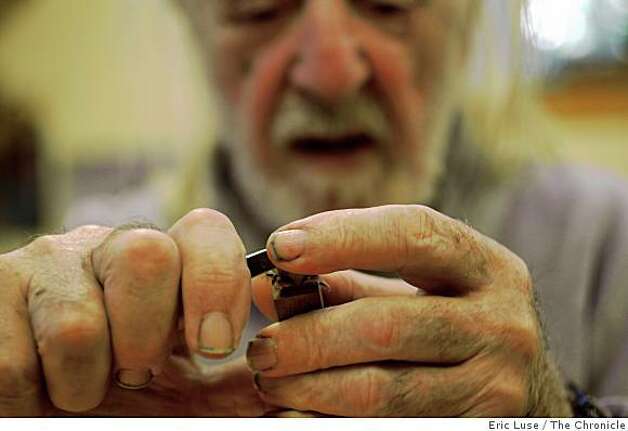

Drawers, built to be slightly larger than their pocket, needed

to be planed down and formed into a subtle wedge-shape, so they come to a smooth

stop just before falling out – something we call ‘let go.' That took about

three solid days.

The doors, also slightly too large (they were the first part

of the cabinet I made, months ago) needed to be cut down until they fit into

the cabinet, then hinge mortises needed to be cut, and the hinges positioned

delicately and carefully until the doors work just right.

And in that process, I discovered one of the doors had

‘wind’ -- essentially, it had twisted slightly at some point and no longer made

a perfect fit with its mate. So that had to be fixed.

But finally, after working until almost midnight Friday, and

scrambling Saturday morning to finish up some final details, I was able to

check off the doors, drawers, back panel, and even had time to fix some dings

and scratches in the finish of the cabinet.

Yes there are parts that are still incomplete, but the vast

majority is done and I met my goals and can go home for the holidays at peace

with my project – which for the first time, actually looks like a real thing.

It also looks beautiful – something I tend to forget in the

long days and weeks and months of toiling over one piece that eventually begins

to feel like a collection of mistakes and fixes. But last night, with the

cabinet sitting on my bench during our woodshop Christmas party, I couldn’t

help but be reminded that it is a beautiful thing, made from precious wood,

that has sentimental value and will stay with me hopefully for the rest of my

life.